Hello everyone! In this article, I will talk about the basic structures that we need to know in order to enable simultaneous, that is, more than one job, to be done at the same time in the Go language. Firstly let’s look at the difference between concurrency and parallelizm breafly.

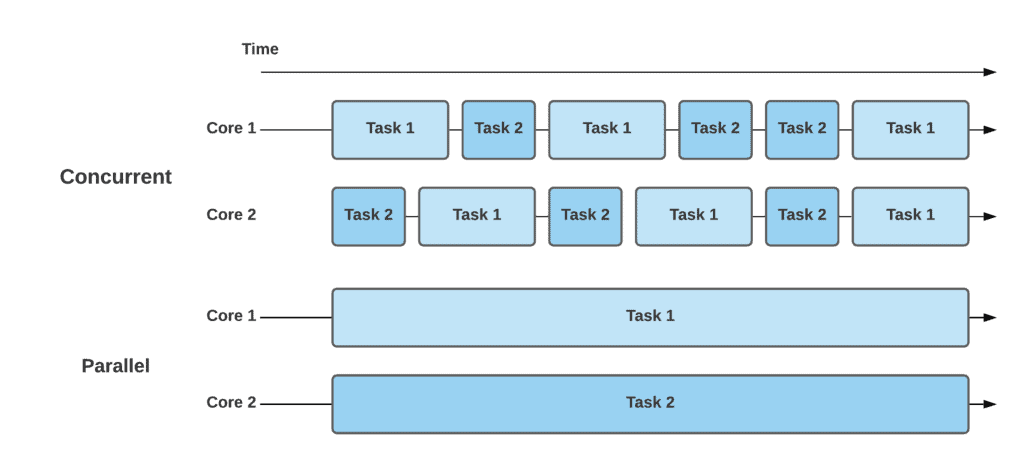

Let’s take a look at how concurrency and parallelism work with the above example. As we can see, there are two cores and two tasks. In a concurrent approach, each core is executing both tasks by switching among them over time. In contrast, the parallel approach doesn’t switch among tasks, but instead executes them in parallel over time.

Goroutines

Thanks to the goroutines, we can enable more than one job to be done at the same time in our go program. In other words, the concept of goroutine can be summarized as each job done concurrently.

Every go program basically has a main goroutine which is formed together with the main function. However, the main goroutine alone may not be sufficient in some cases. For example, let’s say we have save() and calculate() functions that will take a long time. If these functions do not have a goroutine of their own, they use the main goroutine and keeps other processes waiting or waits that use the same goroutine. This is a situation that slows down the flow of the program and creates performance problems. To prevent that, we can run jobs concurrently by creating their own goroutines.

First, let’s examine the problem with the help of an example;

func main() {

start := time.Now()

save(time.Now())

calculate(time.Now(), 5, 3)

fmt.Println("Total time:", time.Since(start).Seconds())

}

func save(start time.Time) {

fmt.Println("Saving...")

time.Sleep(5 * time.Second)

fmt.Printf("The record has been saved - It took %v\n", time.Since(start).Seconds())

}

func calculate(start time.Time, x, y int) {

fmt.Println("Calculating...")

time.Sleep(2 * time.Second)

fmt.Printf("The calculation result:%v - It took %v\n", x+y, time.Since(start).Seconds())

}

func printA() {

for i := 0; i < 50; i++ {

fmt.Print("A")

}

fmt.Println("")

}----------------Output----------------:Saving...

The record has been saved - It took 5.0018482

Calculating...

The calculation result:8 - It took 2.0019639 Total time: 7.0038452As can be seen in the example above, the save function worked and finished after 5 seconds. After that, the calculate function worked and finished in 2 seconds. However, if we look at it, the calculate function waited for the save function for 5 seconds and worked for 2 seconds, so it took 7 seconds in total.

The Go programming language uses the go keyword to create a goroutine and creates a separate goroutine for each job with the go keyword.

Let’s give it a try.

func main() {

start := time.Now()

go save(time.Now())

go calculate(time.Now(), 5, 3)

go printA()

fmt.Println("Total time:", time.Since(start).Seconds())

}----------------Output----------------:

Total time: 0A surprising result is that the total time is 0. This is because our go program creates different goroutines for the save and calculate functions, but terminates the program directly without waiting for them to finish.

If we delay the execution of the main function until the other goroutines are finished;

func main() {

start := time.Now()

go save(time.Now())

go calculate(time.Now(), 5, 3)

go printA()

// 5 seconds is enough time for other goroutines to finish

time.Sleep(5 * time.Second)

fmt.Println("Total time:", time.Since(start).Seconds())

}----------------Output 1----------------:AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA

Saving...

Calculating...

The calculation result:8 - It took 2.0119652

The record has been saved - It took 5.0112932

Total time: 5.0112932----------------Output 2----------------:AAAASaving...

AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA

Calculating...

The calculation result:8 - It took 2.017128

The record has been saved - It took 5.0123579

Total time: 5.0123579In Output1, first the printA function worked and finished. Then the save and calculate functions worked concurrently. The calculate function finished its job in 2 seconds, and the save function finished its job after 3 more seconds.

In Output2, first the printA function worked but not finished yet. Then the save function worked concurrently. Then the printA function finished and the calculate function started to work.

The total running time of our program is equal to the time of the longest running goroutine.

If we examine the outputs in detail, 2 different problems stand out.

1) Outputs are different because we don’t know in what order things will be done. So we can not control the transition between different goroutines.

2) How do we know which process will take how long? How do we make sure the job is done?

Because of the above problems, using goroutines alone is not enough.

I will explain the concepts of wait groups and channels that we need to solve these problems.

Wait Groups:

Its main use is to make sure that a goroutine has finished its job. Waitgroups have 3 basic functions as Add(), Done(), Wait()

var wg sync.WaitGroup

func main() {

//It is used for adding a waitgroup to wait.

//The Number represents the job count. In our case, we have 2 different goroutines to wait (save & calculate).

wg.Add(2)

start := time.Now()

go save(time.Now())

go calculate(time.Now(), 5, 3)

//It is used to wait for the jobs to be done. Simply it waits until the counter is 0.

wg.Wait()

fmt.Println("Total time:", time.Since(start).Seconds())

}

func save(start time.Time) {

fmt.Println("Saving...")

time.Sleep(5 * time.Second)

fmt.Printf("The record has been saved - It took %v\n", time.Since(start).Seconds())

//It is used for the send a finish signal. It decrease the WaitGroup Counter by 1.

wg.Done()

}

func calculate(start time.Time, x, y int) {

fmt.Println("Calculating...")

time.Sleep(2 * time.Second)

fmt.Printf("The calculation result:%v - It took %v\n", x+y, time.Since(start).Seconds())

//It is used for the send a finish signal. It decrease the WaitGroup Counter by 1.

wg.Done()

}

Channels:

Channels are a structure which we can put any type of data and read that data simultaneously. So why do we use it? We use it to move data between 2 different goroutines. At the same time, channels also guarantees that the value sent by one routine to another routine available before it is used.

For example, we are not allowed to put a return keyword in a goroutine function. We can never bind the program’s progress to the main goroutine to a value from another goroutine. Because we get an error due to the possibility of using it without a return value.

NOT ALLOWED //It gives an unexpected go keyword error.

func main(){

result:=go calculate(5, 3)

fmt.Println(result)

}

func calculate(start time.Time, x, y int) string{

fmt.Println("Calculating...")

time.Sleep(2 * time.Second)

return fmt.Sprintf("The calculation result:%v\n", x+y)

}That’s why we use channels. We channel the value and read that value in the other goroutine.

to write a value into channel

channel <- valueto read a value frm the channel

value <- channelExample usage:

func main() {

myChannel := make(chan string)

var val string

go calculate(5, 3, myChannel)

val <- myChannel

fmt.Println(val)

}

func calculate(x, y int, channel chan string) {

fmt.Println("Calculating...")

time.Sleep(2 * time.Second)

channel <- fmt.Sprintf("The calculation result:%v\n", x+y)

}

Its important to note that, you can only read the value in a channel which is written by other goroutines. So you can not do both write and read in one channel at the same time. Because channel uses a lock mechanism.

NOT ALLOWED //It gives fatal error: Deadlock!

func main(){

myChannel := make(chan string)

//Writing

myChannel <- "Value"

//Reading

fmt.Println(<-myChannel)

}

I actually have a lot to tell about this subject, but I think it’s been a long enough article. Thank you for giving a time. I hope I was helpful. See you in next article 🙂 🙂